Draw Your Weapons: Urs Graf and the Self-Preservation of Drawings

Sarah C. Rosenthal

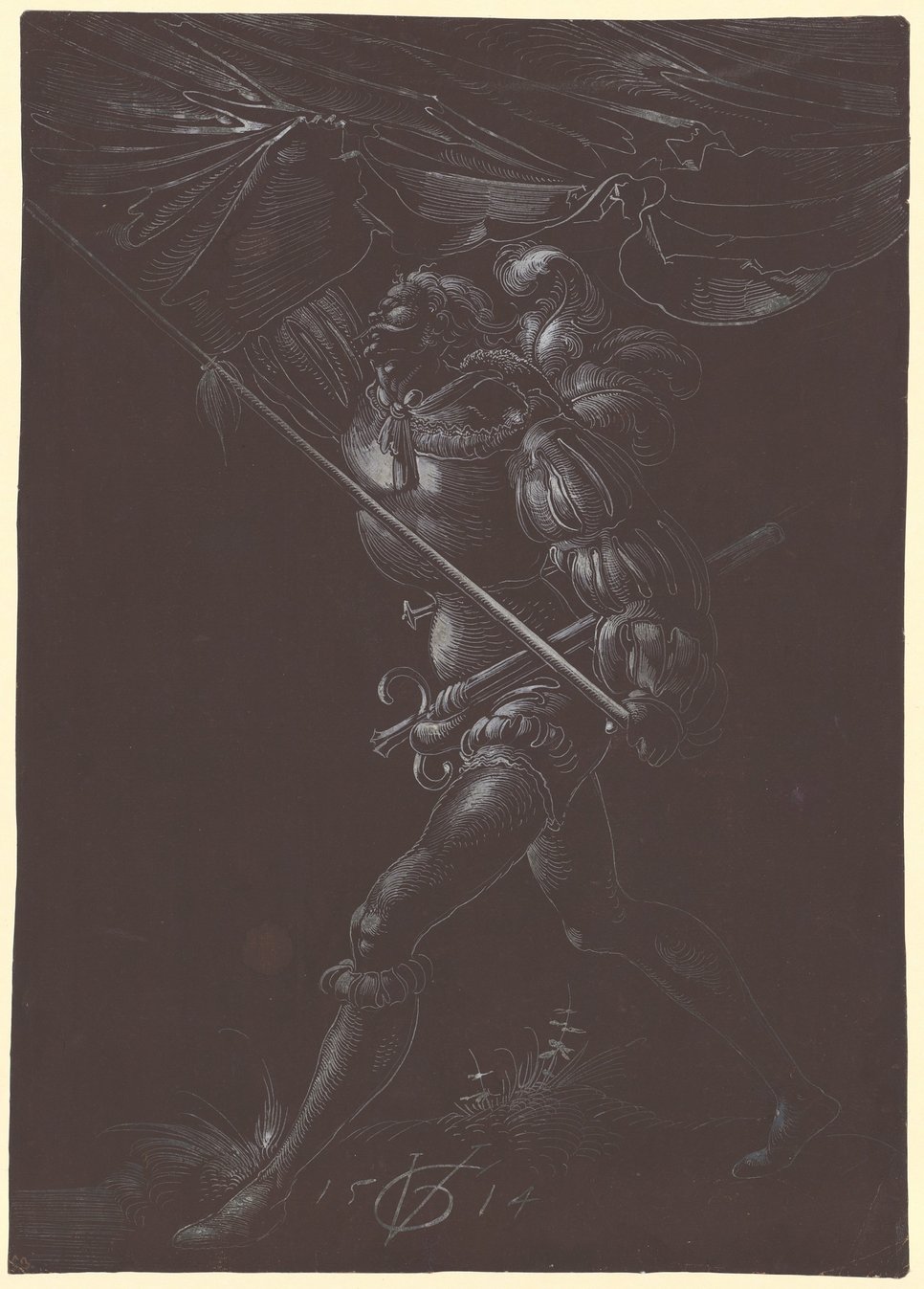

Centering the early sixteenth-century Swiss artist and mercenary soldier Urs Graf, my dissertation investigates the creation and collecting of art as forms of long-term self-preservation. Working and fighting during the Italian Wars, the Reformation, and a period of general sociopolitical change in Basel, Graf would have been acutely aware of the threats to life and legacy all around him. Creating metal objects, painted glass windows, prints, and designs for coins for patrons from the clergy, the book publishing industry, and the municipal government, he could disseminate proof of his artistic skill. But it was in pen and ink line drawings on paper—many kept in his own collection and surviving in near flawless condition—that he could protect and preserve the signs of his power and ability. Graf was demonstrably aware of the importance of signs of violence and authority, from weapons and battle standards to coats of arms and artistic monograms. Thus, I argue, art was a space to tune the balance between outward displays of power made vulnerable due to the decaying effects of battles, conquest, or simple material processes and private self-protection that might go unwitnessed. A private collection of drawings was here like an armory, kept in reserve but ready for action when the opportunity arose.

While at the Hertziana, I worked on my dissertation and concurrently researched an aspect of the material culture linking the papacy as political entity to the Swiss cantons: the so-called Juliusbanner of 1512. During a time of heated conflict up and down the Italian peninsula, Pope Julius II and Kardinal Matthäus Schiner gifted these precious presentation banners to the Swiss in thanks for their military support. The flags thus raise important questions about the afterlives of objects made to commemorate mutable allegiances. With the support of the Lise MeitnerGroup, I visited collections and met with curators and conservators across Switzerland to understand the banners’ histories and their current condition. I presented preliminary findings at the Hertziana conference “Art in Times of War and Peace: Legacies of Early Modern Loot and Repair.” In a talk titled “Loot/Tool: Urs Graf, the Juliusbanner, and Inversions of Loot”, I discussed how, despite the fragility of the objects and their known status as targets of looting, the Juliusbanner represented an attempt by the papal regime to secure authority in the Swiss lands in perpetuity. This appeal to eternity – written into the legal privilege for fabrication of the banners – is key, given the period fixation on contingencies of and inversions of fortune. I argued that case study illuminates a unique aspect of visual and material culture within the political theater; they could open an avenue to pursue longevity where otherwise death and regime changes ruled. At the same time, they also demonstrated the futility of such a pursuit. I am now preparing to publish texts based on my research.