Diagrams in Early Modern Science: The Case of Magnetism

Christoph Sander

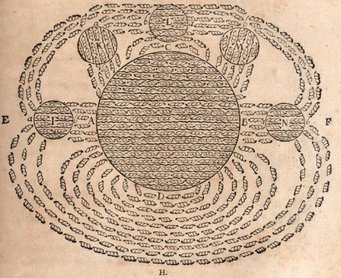

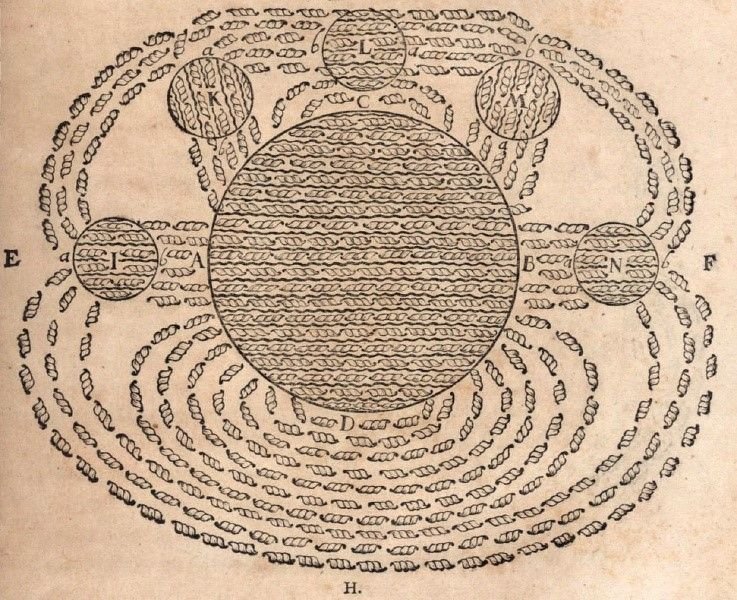

This project examines the production, typology, and use of diagrams in early modern science. The case study focuses on pre-modern attempts (1300–1650) to represent magnetism through diagrams and is intended to serve as a blueprint for other historical research areas.

After centuries of predominantly logical and semantic analysis in natural philosophy, new forms of diagrammatic representation and new techniques for their material production were developed in the early modern period. As a result, diagrams became “an important tool of science in the European Renaissance” (Martin Kemp 1997).

But what the historical actors actually meant by “diagram,” what visual means they used that can be called a “diagram” from today’s perspective, and what these diagrams were used for, remains largely unexplored. Approaching these questions involves reflecting on the media that “transmit” the diagrams, on the role of printers and artists, on the interaction of text and diagram, but also on the conceptual premises of the underlying theories as well as on the practices or functions for which the diagrams were used.

Why a case study devoted to magnetism? This field of research turns out to be one of the most important early modern thematic areas in which diagrammatic forms of argumentation were applied. Like modern physics textbooks, early modern treatises do not just illustrate pieces of magnetic iron ore, but rather attempt to visually represent experimental findings about the invisible physical properties of magnets.

As a result, magnetism represents one of the earliest cases in which experiments, instruments, machines, mathematical calculations, and geometric abstractions were depicted in diagrams, not only in terms of geometric relationships, but also in terms of physical objects and forces.