Authorial Control/Artistic Agency: Graphic Techniques and Intaglio Methods in Eighteenth-Century Scientific Image-Making Practices

Alicia Hughes

During the mid-eighteenth century, intaglio techniques that imitated the style, technique, and medium of drawing became popular in Britain and France. This development was a result of patriotic and commercial publishing projects that aimed to produce printed reproductions of drawings by important contemporary artists and Old Master drawings in notable collections. These intaglio methods included an increased use of etching and the development of the crayon method and stipple engraving that enabled engravers to translate the expressive, spontaneous qualities of artists’ original style and technique into the graphic mediums of chalk and wash. They produced ever-closer approximations of the appearance of drawing media in print.

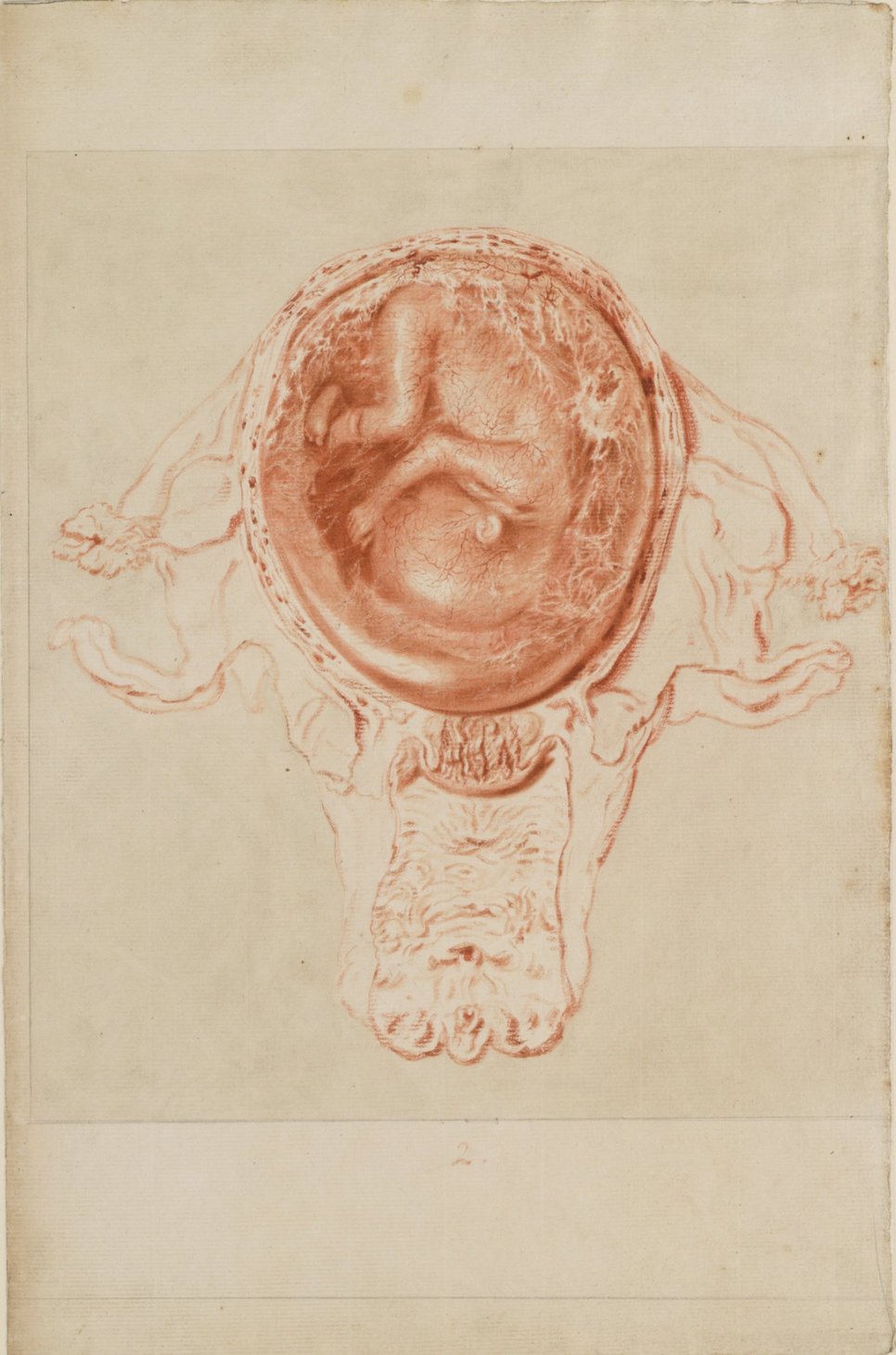

These publications were largely intended towards developing artistic drawing practices, but the engravers who worked on them did not work in isolation. Also, scientific practitioners relied on these engravers to reproduce commissioned drawings in print. Anatomists such as the Scottish physician and male midwife, William Hunter (1718–1783) commissioned a large team of engravers to produce engravings of anatomical drawings made by artists such as Jan van Rymsdyk for his Anatomia uteri humani gravidi tabulis illustrata (1774). The detailed, hyper-naturalistic engravings within Anatomia and Hunter’s claims of ‘truth to nature’ have fascinated and preoccupied scholars, but the reproduction and translation of Rymsdyk’s slight, sketchy graphic chalk outlines onto the printed plates affected the book’s visual language in a subtle but significant way. Focus on standardisation of style in printed images has eclipsed more diverse elements in scientific images and obscured how authors rhetorically responded to tensions around mediated authorship. This project will investigate the extent to which intaglio techniques that aimed to faithfully imitate graphic techniques and mediums manifested themselves within scientific printed images during the eighteenth century. How significant were wider printmaking trends to the production of printed scientific images in the eighteenth century? Did these methods appear in illustrated publications outside of Britain and France, for example, in countries such as Italy and Holland? How did scientific authors rhetorically account for the use of these techniques? And finally, did intaglio techniques that foregrounded the original graphic technique strengthen or undermine the epistemic claims of the images?