Ancha Ñaupa Pacha: The Creation of a Global Antiquity in the Early Modern Andes (1550s–1650s)

Juan Carlos Garzon Mantilla

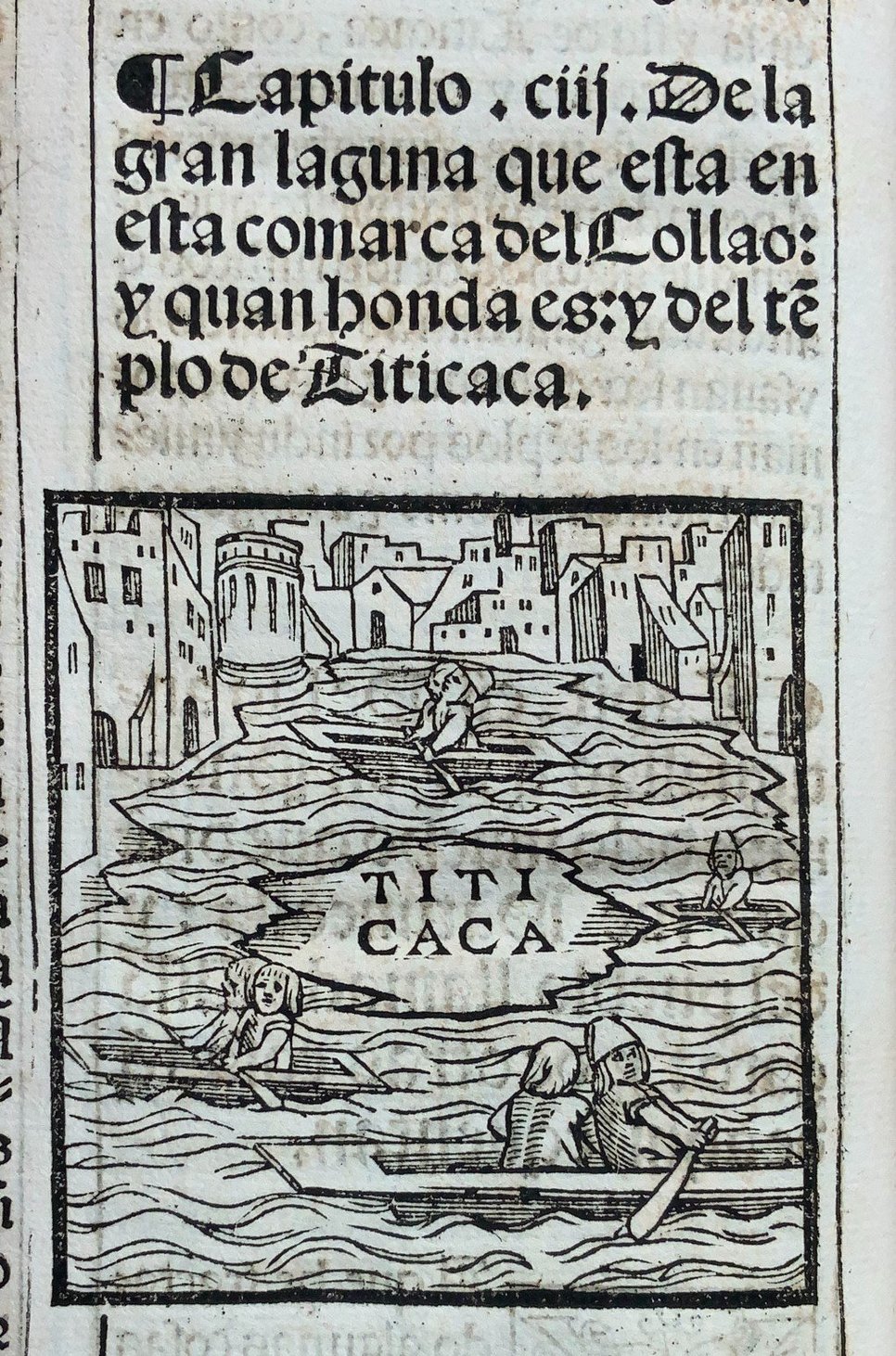

The project argues that a novel, global understanding of antiquity was imagined in the historical writing and arts of the Early Modern Andes based on cross-cultural interpretations of indigenous pre-Columbian material culture and Andean nature. This groundbreaking, interdisciplinary study uncovers how indigenous pre-Columbian archaeological landscapes and Andean geological environments became the fundamental archives of a new form of historical thought that created a global antiquity from the Early Modern Andes, and set the cornerstones for the development of the modern archaeological paradigm of the ‘Ancient Americas.’ Challenging the Eurocentrism that reduced the Americas to a ‘world without history’, it demonstrates that the Americas were instead seen in the early modern period as a world full of the most ancient history. This perception forced a thorough reinvention of the deep past of the world.

Ancha Ñaupa Pacha delves into the vast corpus of historical writing and visual arts of the Early Modern Andes – a corpus shaped by the tumultuous processes of conquest and colonization – to explore the innovative efforts of indigenous, mestizo, Creole, and European scholars and artists in the Andes who faced the unprecedented task of deciphering pre-Columbian archaeological geologies to reveal how the ancient Americas were connected with the most distant past of the Mediterranean and the Middle East.

In doing so, Early Modern Andean scholars combined territorial exploration and principles of Renaissance antiquarianism with indigenous forms of historical knowledge. Classical, and biblical narrative traditions supplied further ingredients with which to interpret the ancient Andean past and to integrate into its archaeological and geological framework pre-Columbian buildings, ruins, fossils, monoliths, megaliths, and mythological flora and fauna. Their epistemological experiments resulted in novel visual and written historical interpretations and imaginings, thus creating a new ancient history that was both distant in time and world-encompassing in scope: a global antiquity.

During my appointment at the Bibliotheca Hertziana as a Census x Hertziana fellow, I developed and presented two chapters of my project. The first titled “Tiahuanaco/Ruins” explored the earliest Christian interpretations of the Tiahuanaco Ruins in the north of current-day Bolivia and, in doing so, connected these archaeological accounts with the Quechua understanding of ‘fragment’ (huaqui). I argued that Tiahuanaco was an example of early modern efforts at the reconstruction of fragmentary and ruined historical knowledge. The chapter advances a new interpretation of the art historical terms ‘ruin’ and ‘fragment’ – recently debated in many scholarly works – from a perspective based on the indigenous Americas. The chapter titled “Pacaritambo/Genealogies” analyzes how the idea of Inca history was integrated into the art historical and historiographical canon by giving it the form of a genealogy of successive kings. By interrogating the very idea of genealogy, I develop the thesis that this idea originated in an Inca myth that, contrary to other indigenous myths, was not challenged by Christian missionaries but instead transformed into a fundamental way of ordering and imagining the ancient history of the Andes in a way similar to the histories of Christian kingdoms.