Portatrici, Lavandaie, Cucitrici: Picturesque Modernism and the Image of the Italian Woman at Work

Anna Aline Mehlman Dumont

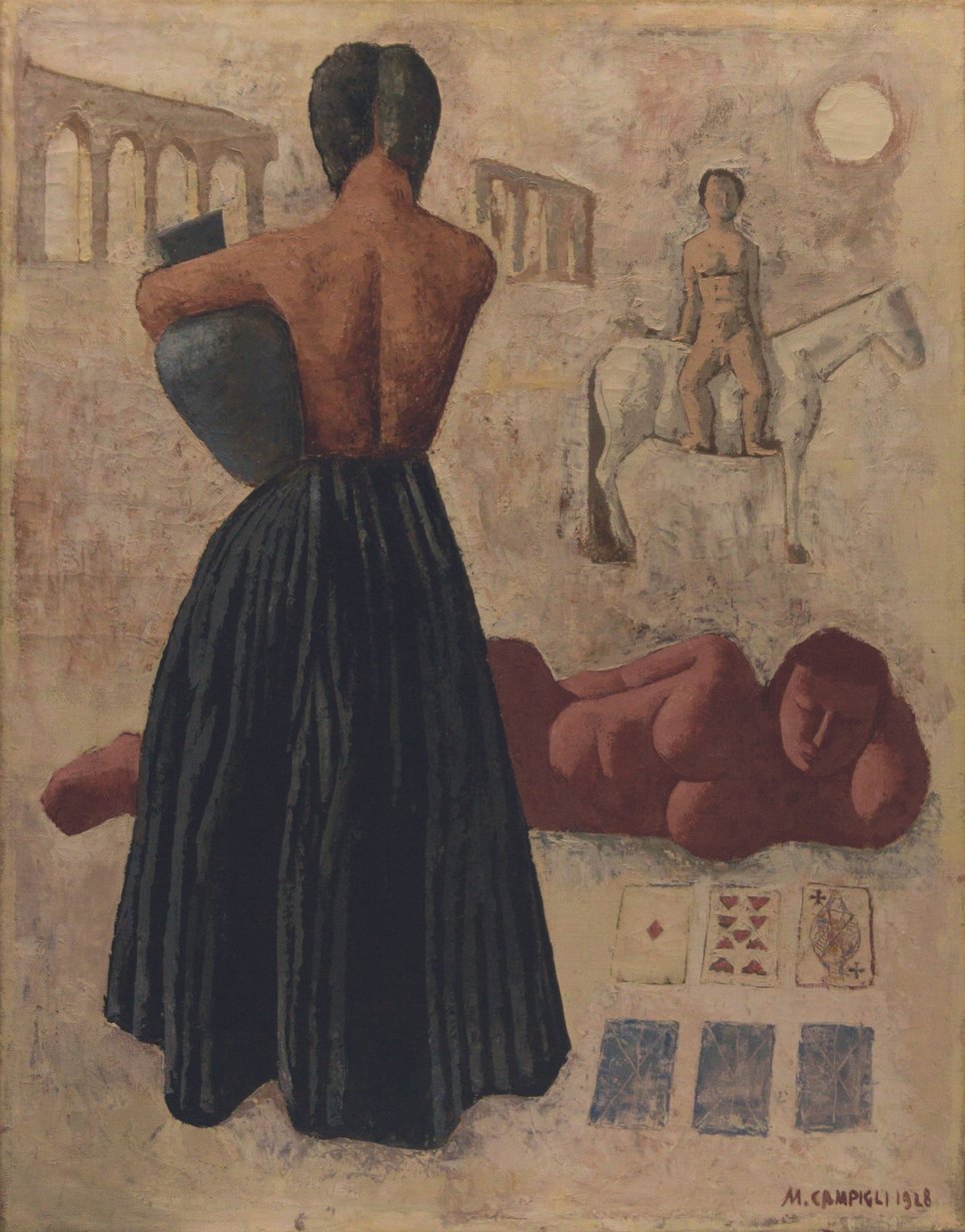

My project centers on allegorical depictions of women’s work as it features in the art produced by Novecento artists such as Mario Sironi and Massimo Campigli during the Fascist ventennio. Romy Golan refers to these massive wall paintings of this period as “monumental fairytales”, and this dreamy mystery infuses the paintings of water carriers and weavers made by Campigli, Sironi and others in the 1920s and 1930s. My project, however, traces a new genealogy of these depictions of women’s work, considering the fin-de-siecle history of ethnographic image collecting undertaken by art critics and social reformers invested in preserving forms of Italian life seen as under threat from modernity. I draw on photographic collections of women sewing, washing, and carrying water amassed by activists such as Elisa Guastalla Ricci, and published in art periodicals like Emporium and The Studio to argue that such picturesque depictions are the product of anxieties about the place of women’s domestic labor at the moment of Italian industrialization.

This study treats the works at issue not simply as iconographic traces but as constructors of the social and political world. This is especially true for objects in public space, from the murals, mosaics, and stained glass of state commissions for pavilions and public buildings to architectural ornament on the streets of Italian cities, as for example the allegorical figures of a male labor and female salus flanking Antonio Maraini’s portal for the Cassa delle Assicurazioni Sociali building in Milan (1930), reproduced as a kind of male and female set in the pages of the Fascist women’s magazine Lidel in 1934. Just as Ricci’s photographs and the Risorgimento-era paintings of the Macchiaioli art movement sought to establish a new Italy on nostalgic, nationalist terms, the art of the ventennio sought to enact an ambiguous policy of gendered work. While the movement began with many militant female supporters, by the 1930s the rhetoric was increasingly preoccupied with women’s reproductive capacities. Yet women’s labor was cheaper than men’s, thanks to unequal wages, and the regime understood that the policy of autarchy, especially in the industrial textile sector, depended entirely (if inconveniently) on the female workforce. The expression of these complex gendered political goals in the aesthetic debates of the Fascist period remains understudied, and this project is among the first to situate these monumental depictions of work within a longer tradition of the politics of gendered labor in Italy.

The final portion of my study continues beyond the large-scale paintings of male masters of the Novecento, asking what new histories of Italian art and women’s work can be drawn by focusing attention on female artists who have long been treated as marginal. In a counterpoint to the obtuse mysticism of Campigli, Martini, and Sironi, I follow this strain of depicting women’s labor into the postwar in the work of Edita Walterowna Broglio and Leonor Fini, who produced surreal images of women in which the visual codes of women work are scrambled: instead of weaving, women wrap yarn around each other’s wrists; instead of washing clothes, women submerge cloth in water to unknown and mysterious ends. In the surrealism of Fini and Broglio’s alternate depictions of women’s work, it is possible to imagine a new approach to this imagery emerging, one in which women’s bodies are no longer the subject of wonder but agents of their own strange ambiguities.