The Alphabet of Nature: Languages, Science and Translation in Early Modern Europe

Sietske Fransen

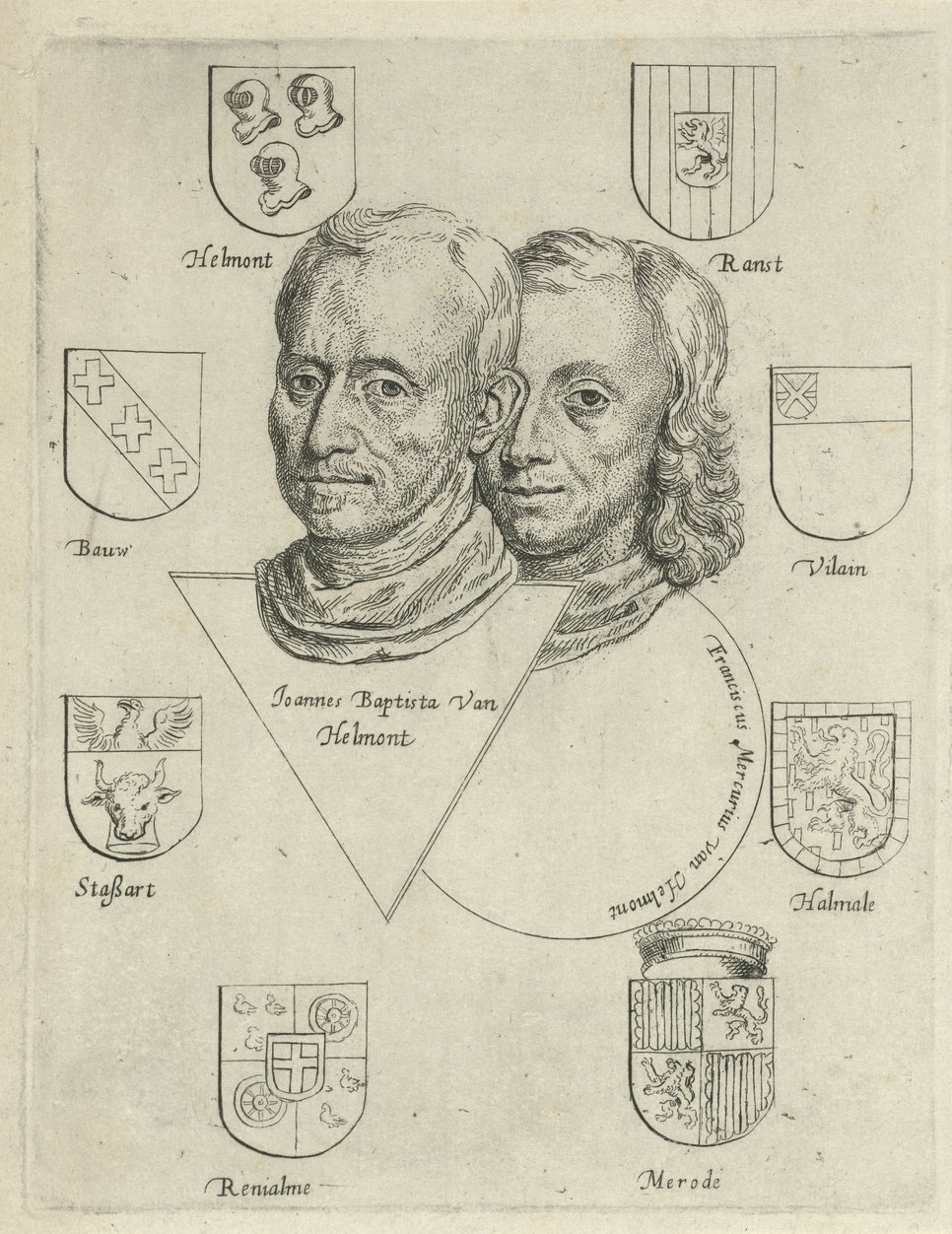

Portraits of Jan Baptista (in the front) and Franciscus Mercurius van Helmont, by Cornelis de Man, paper, 1648. © Rijksmuseum Amsterdam

“I write this book in my mother tongue, so that those who will read it, will understand that the truth does nowhere appear more naked, than where it is stripped of all its jewelry.” Jan Baptista van Helmont (1579–1644), who wrote this sentence in the introduction to his medical works (Dageraad, ofte nieuwe opkomst der geneeskonst, Amsterdam 1659) was determined to publish medicine and science in his mother tongue, Dutch, to give the clearest possible account of his ideas. Soon, however, disillusioned by the limited capacities of his own language, Helmont then decided to write most of his works in the more common language of science at the time – Latin.

This book project focuses on the interface between these two parallel worlds, the one constituted by the mother tongue, the other by the professional language of learning. By delving into the example of the Flemish natural philosopher Jan Baptista van Helmont, his son Franciscus Mercurius (1614–1698), and numerous other early modern Europeans, this book will examine how authors of scientific and medical texts tried to navigate a passage back and forth between their languages. Covering the full span of the seventeenth century, it will reconstruct how the elevation of vernacular languages to the status of functioning languages for science came at the cost of a common language and therefore stimulated the renewed search for a universal language of science. The seventeenth-century authors searched through languages, metaphors, and (mental) images, and even studied the morphological forms of the thorax in a quest for a mode of expressing their ideas about nature as precisely and accurately as possible.

This book project focuses on the interface between these two parallel worlds, the one constituted by the mother tongue, the other by the professional language of learning. By delving into the example of the Flemish natural philosopher Jan Baptista van Helmont, his son Franciscus Mercurius (1614–1698), and numerous other early modern Europeans, this book will examine how authors of scientific and medical texts tried to navigate a passage back and forth between their languages. Covering the full span of the seventeenth century, it will reconstruct how the elevation of vernacular languages to the status of functioning languages for science came at the cost of a common language and therefore stimulated the renewed search for a universal language of science. The seventeenth-century authors searched through languages, metaphors, and (mental) images, and even studied the morphological forms of the thorax in a quest for a mode of expressing their ideas about nature as precisely and accurately as possible.