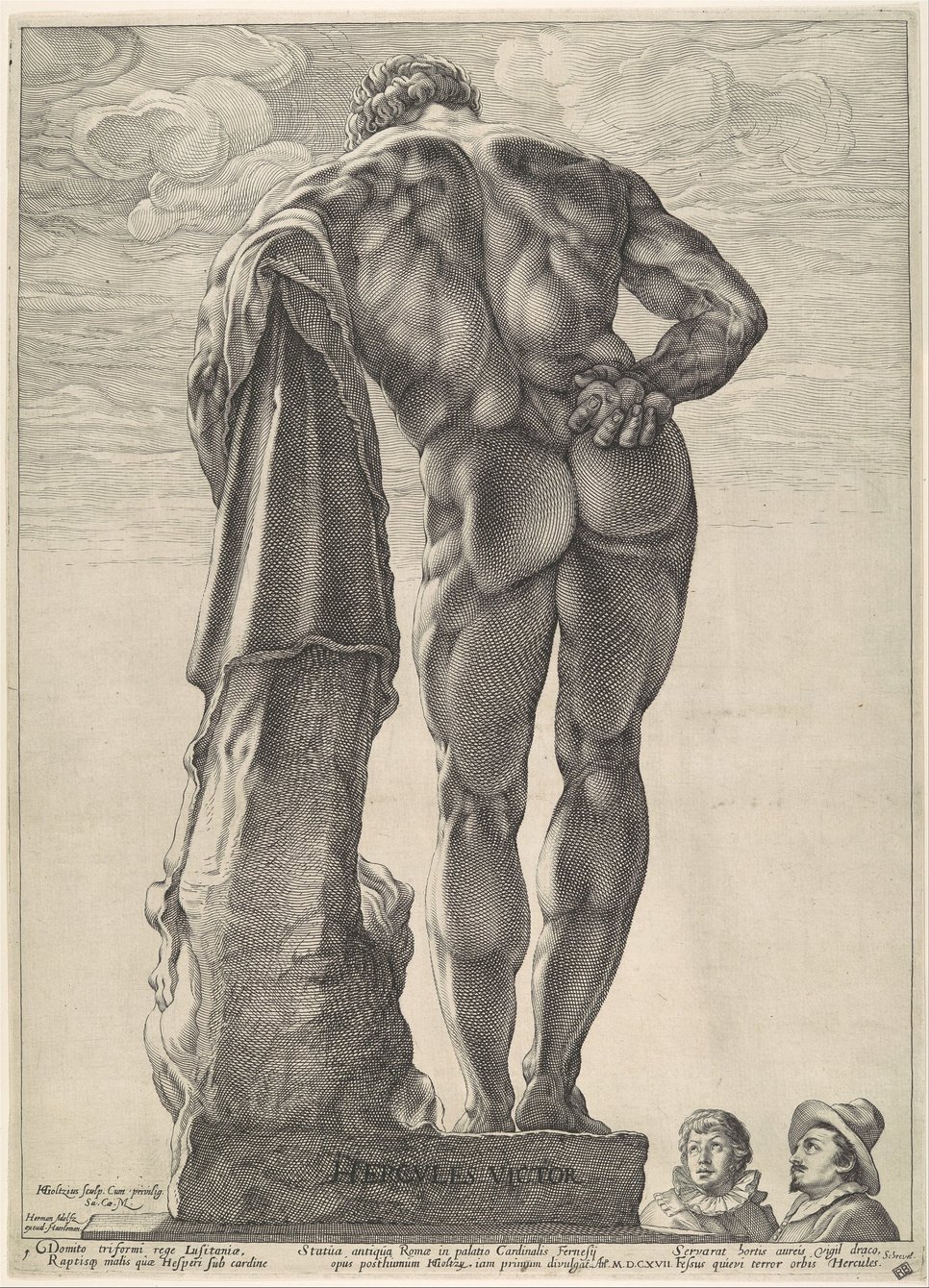

True Lies: Restorations, Reproductions, and Fake Antiquities

Barbara Furlotti

In his Discorsi sopra le medaglie degli antichi (1555), Enea Vico addresses the problem of false antique coins by identifying three categories of forgeries: the ‘fully ancient’ deceits, obtained by either heavily reworking ancient coins or pasting two of them together; the ‘partially ancient’ frauds, made with old metal struck with modern dies; and the ‘completely modern’ coins, cast with new metal. Compared to Vico’s subtle classification, the definition of forgery provided by the Oxford English Dictionary – ‘The making of a thing in fraudulent imitation of something’ – sounds simplistic. Contemporary binary descriptors, such as prototype/replica and original/fake, also exemplify our difficulties in grasping the Renaissance’s nuanced approach to forgeries and manipulated antique pieces. My project stems from this conceptual chasm and answers questions regarding the impact that Renaissance restoration practices had on the reception of antiquities, and the role played by forgers and antiquarians in disseminating alternative versions of the past. During my two months in Rome as part of my Census Fellowship (January-June 2024), I presented this research at a seminar at the Hertziana.